email: latenightpickwick@gmail.com

In this space, the Pickwick Drive-In examines motion pictures through which a singular artist played an important part, large or small. Four Seasons is an exploration of four films — four brief moments, like the seasons themselves, representing birth, growth, time, and finality — with the contribution of a unique star, whether in front of the camera as a movie star; playing a supporting role in the production’s cast; or behind the camera as a cinematographer, director, writer, and more.

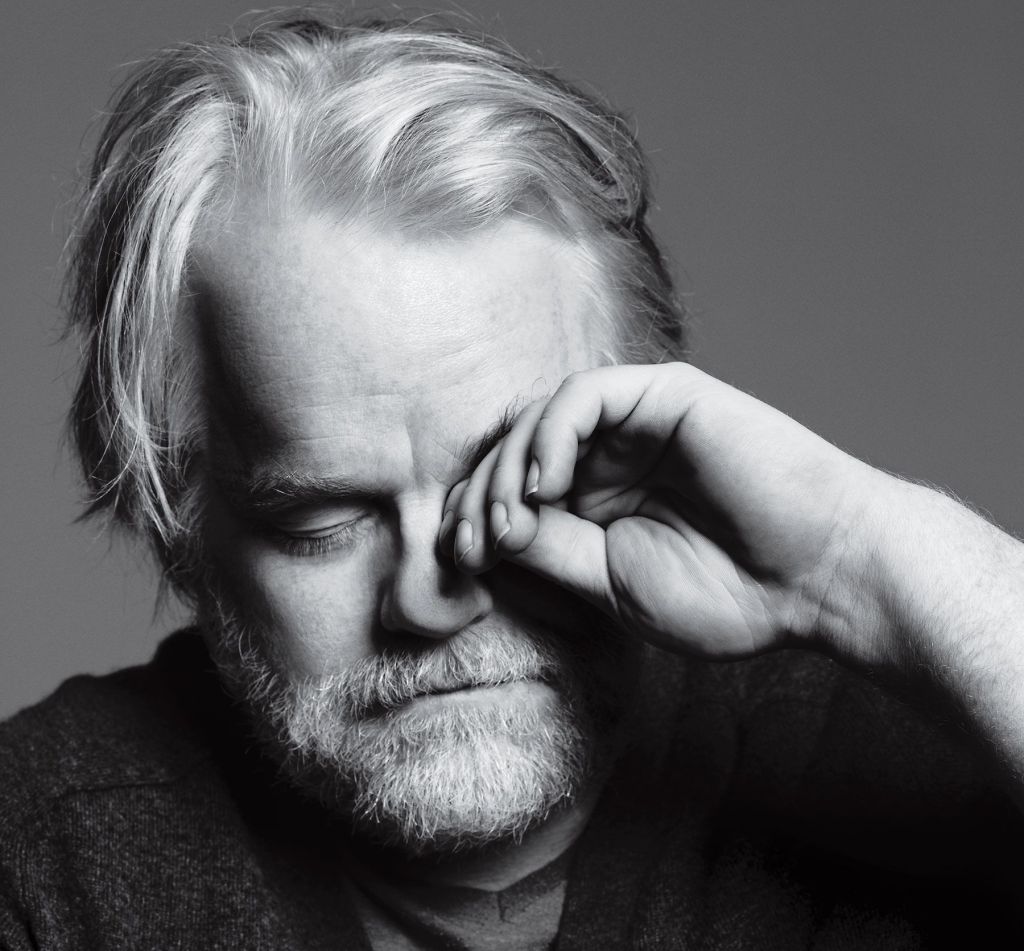

This month, the Pickwick rolls back the celluloid reels, showcasing four motion pictures starring Philip Seymour Hoffman — who was born in 1967 & passed on February 2nd, 2014 — exploring the movies of which Hoffman played a memorable role.

S P R I N G

C O M E D Y

* * * *

Punch-Drunk Love

d. Paul Thomas Anderson | dp. Robert Elswit | s. Paul Thomas Anderson | 2002 | R | 95 minutes

* * * *

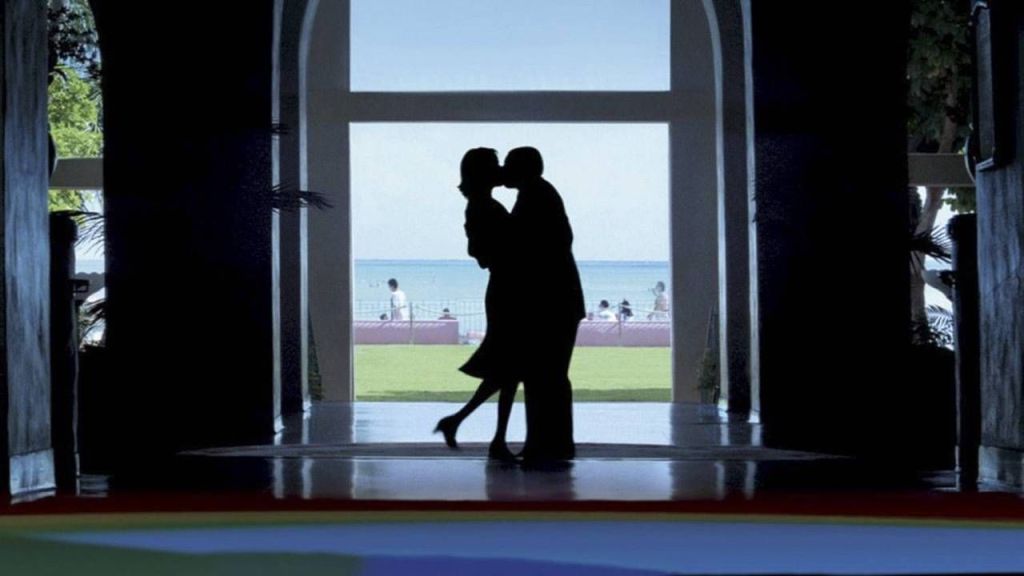

On the heels of his directorial debut Hard Eight (1996), the critical acclaim of his sophomore effort Boogie Nights (1997), and his polarizing ensemble cast film Magnolia (1999), Paul Thomas Anderson’s fourth film tells perhaps one of the most unique stories of romance that you’ve ever seen, starring Philip Seymour Hoffman in a supporting role as Dean Trumbell, an aggressive mattress store owner who supervises a phone sex operation meant to exploit its lonely customers for more money. And struggling businessman Barry Egan (Adam Sandler) is one of those lonely customers.

Socially awkward and capable of violent outbursts that result from his deep-seated feelings of isolation, Barry’s already challenging existence is upended when he discovers a malfunctioning harmonium and falls in love with the enigmatic Lena (Emily Watson).

In singular PTA (Paul Thomas Anderson) fashion, Punch-Drunk Love is a love story as awkward as Barry Egan himself, a film about romance that is as unpredictable as Barry’s behavior.

I discovered Punch-Drunk Love at a perfect time in my life, jarred in the best possible way by Boogie Nights, with its ability to tell an affirming story of human potential through the lens of adult films. Yet I wasn’t prepared for a romantic comedy like Punch-Drunk Love. What I knew of cinematic romance was somehow linked to Tom Hanks: an otherworldly love affair with a mermaid; a star-cross’d connection made over a radio call-in show; an online chat room friendship that turned into lifelong bliss. But no would-be romantic comedy protagonist was somehow as broken as Barry Egan – and I empathized with his character in ways in which I was only then beginning to understand. I don’t think that I’m out of line when I write that we all feel a little lost when it comes to love, but PTA’s exploration of loneliness and longing brought into focus – for me – the singular nature of romance lying at the heart of the film, at first inexplicable yet ultimately undeniable.

The bouts of violence that characterize Barry’s personal life are emblematic of the violent carnage that brings the broken harmonium into Barry’s life. Both appear to be incapable of making something harmoniously musical, and Barry’s efforts to unearth something musical from the windy depths of the harmonium are rather similar to his efforts to discover something peaceful from his own character’s depths. Romantic comedies have consistently discovered a character seemingly out of control – love-lorn, widowed, or disenfranchised like Tom Hanks’ heartwarming heroes – but PTA’s film fully highlights the opportunity that can come out of a malfunctioning human being.

And if Barry can discover something soothing atop the black & white keys of the harmonium, he can discover something capable & content & deserving of love atop the multi-colored complexities of his own self.

Perhaps, then, so can we.

As demonstrated in the motion picture, the point is not necessarily to stumble across true love like the fairy tales have told us; rather, the point is to take advantage of the accidents that the world drops before us. Sometimes, serendipity is discovering a lifetime’s worth of airline miles through the purchase of pudding cups. And sometimes, the discovery of a broken harmonium teaches us to learn how to play music like we’ve never played before. Both discoveries may encourage us to stand up to a bully who threatens to get in the way of our search for love.

That’s that.

Just say it.

That’s that.

* * * *

Punch-Drunk Love is streaming on the Criterion Channel.

S U M M E R

A C T I O N

* * * *

Mission: Impossible III

d. J.J. Abrams | dp. Dan Mindel | s. Alex Kurtzman & Roberto Orci, et al. | 2006 | PG-13 | 126 minutes

* * * *

My uncle was a huge fan of Mission: Impossible, and – despite his best efforts, and yes, I chose to accept it for at least a moment – I could never get into the espionage-based television series. It was truly an impossible mission, getting me to warm up to the series, guided by a sparkling fuse though it was. Like Star Trek, Dark Shadows, The X-Files, and more, the mountain of mythology was intimidating to me. Sure, I could start at the very beginning, but I still felt that I would die long before I ever caught up.

But I was attracted to a film that was somewhat disconnected from the television series. And who isn’t a sucker for a good action movie? Director Brian DePalma’s Mission: Impossible (1996) seemed more like Mission: Probable, to me — a motion picture that went well beyond the shadowy interplay of other spy movies, a movie that brought urgency to the traditional cloak & dagger narratives of the big screen.

M:I was not of the same ilk as action movies starring the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Steven Seagal, even Jason Statham today. The adventures of Ethan Hunt – played by Tom Cruise – possessed a markedly intelligent approach to what could be called an action film, at times making the espionage of James Bond seem like weekday afternoon television fare. Upon seeing the film three times, I was in love with this seemingly new (to me) action movie bent.

Things were about to heat up, because in the third installment of the M:I movie franchise, Alias wunderkind J.J. Abrams would team up with two screenwriters who would bring – for me – more depth than had been witnessed in Hunt’s first two adventures.

Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that the line between Hunt’s professional & personal lives was about to become very blurred. Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that one of Hunt’s most valued recruits would be killed in a most unimaginable manner.

Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that no M:I villain had been so singularly personified as he had been through the talent of Philip Seymour Hoffman.

When IMF operative Hunt – deep in the throes of teaching agents in the classroom rather than leading them in the field, deep in the throes of getting engaged & settling down – learns that one of his best trainees (Kerry Russell, the talent behind Abrams’ TV series Felicity) may have been taken hostage by weapons dealer Owen Davian (Hoffman), Hunt is tasked with tracking down a sinister piece of mystery tech in order to save the life of his bride-to-be.

What begins to work so wonderfully within the franchise here is that Hunt – like Bond – has his proportional Q and his M to assist him in what should be an impossible mission. His support comes in the personality of cyberfreak Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), with the additional introduction of technician Benji (Simon Pegg). Both would go on to assist Hunt through the franchise’s (at the time of this publication) eight films.

But with M:I III – from a screenplay by Alex Kurtzman & Robert Orci (who would go on to work with Abrams & his Bad Robot studio on Star Trek (2009) and later with director Jon Favreau’s sci-fi western Cowboys & Aliens (2011)) – Hoffman embodies a more diabolical villain than seen in the franchise’s first two films.

Appearing for a little more than 20 minutes of the film’s over two-hour runtime, Hoffman’s Owen Davien is methodical. Owen Davien is cold. Owen Davien is exacting in the war that he wages against Ethan, making the attack on Ethan’s life a plot point that would follow Ethan for future M:I films to come. That’s what ultimately makes M:I III so captivating: how close to home the motion picture goes, how dangerously close to the end of Ethan’s life the movie comes.

True, some elderly relatives of Ethan were targeted by IMF in DePalma’s first film entry back in 1996, but there was no real gravitas, no real peril, there. The couple was practically an afterthought – even to Ethan – but the introduction of Julia (Michelle Monaghan) brought a level of humanity to the franchise that the first two impossible missions hadn’t glimpsed, even (if only briefly) opening up Ethan Hunt’s universe with supporting characters with recognizable faces like Aaron Paul, Bellamy Young, and Abrams loyalist Greg Grunberg. This window dressing may appear at first superfluous, but it manages to bring a complexity to widescreen villainy that wouldn’t be replicated until some of the James Bond films starring Daniel Craig.

The mission – and we chose to follow their adventures – may not be impossible …

… But M:I III demonstrated that espionage films had come a long, long way since the days of Pussy Galore.

* * * *

Mission: Impossible III is streaming on Paramount+.

A U T U M N

D R A M E D Y

* * * *

Almost Famous

d. Cameron Crowe | dp. John Toll | s. Cameron Crowe | 2000 | R | 122 minutes

***

Had I grown up in the heyday of the 1970s or the 1980s, I fully contend that I would have been a young 12-year-old who told people that I wanted to be a rock star when I grew up.

And I’d say it without irony.

I would want to be Mick Jagger. Or David Lee Roth. Or maybe even Jon Bon Jovi.

Not a musician. A rock star. There’s a distinct difference. And I didn’t need writer-director Cameron Crowe’s 2000 film Almost Famous to teach me that difference, but that isn’t to suggest that the film didn’t help.

In the movie, well above-average student William Miller (Patrick Fugit) dreams of one day being a rock journalist. But when he gets the chance to tour with a potentially successful rock band (fronted by Jason Lee & Billy Crudup), he becomes seduced both by the touring lifestyle and the fans (which include “band-aid” – not groupie – Kate Hudson) – like him – that fuel rock star devotion.

But the illusion of stardom is quickly brought into stark contrast as William sees the day-to-day life of so-called “rock stars,” and he’s aided by the more experienced, drug-addled music journalist Lester Bangs (Philip Seymour Hoffman), who steadfastly encourages him to tell rock band Stillwater’s true story while on the road, despite William’s fandom for a rock band that he has grown to love – despite William’s need to simply tell the story, from the outside.

If only it were that easy.

The film plays with the notion of identity throughout. As William comes to understand that he’s not as old in years as his mother (Frances McDormand) has led him to believe, he also assumes the identity of an older, more experienced journalist so that he can secure a job with Rolling Stone magazine.

Take a promising young man and place him in high school with students years older than him — and you’ve got stories to tell. Take a high school journalist and send him on the road with an immature rock band overwhelmed with women, drugs, and partying — why, the obituary writes itself.

This motif recurs throughout the film frequently, even on smaller scales. William’s rebellious older sister Anita (Zooey Deschanel) responds to the apparently dysfunctional home her mother has built by running away to become an airline stewardess, not content to be the young woman whom she is, longing to be the young woman she could be. In a conversation that almost sounds superfluous at first to character-building, William confesses to Lester Bangs that he appreciates musician Lou Reed’s earlier material than the music he’s currently producing. “In his new stuff, he’s trying to be Bowie,” William says. “He should be himself.” So too should Penny Lane (Hudson) — a young woman who has created an identity for herself on the road that will protect her from the heartache she will potentially face while romantically pursuing would-be rock stars like Russell Hammond (Crudup).

But just as Penny Lane has no legitimate future with Russell, so too is a life-changing trip to Morocco not in the stars for Penny Lane & William, no more than a story that they tell themselves to keep the tour bus wheels turning, to keep the ride going.

Yet existential crises like these are what give momentum to Almost Famous & its wandering soul. The music, the fashion, and the backstage rider with steak & other luxuries — that’s simply scenery.

And for this film to work, no existential journey of any kind needs more than the ragtag rock band that takes to the stage every night: Stillwater.

Through this band, the audience likely has a little more true confessional than a fictitiously-designed group of musicians. To those who have learned an instrument and created a brotherhood with like-minded artists and walked onto the stage and performed before throngs of fans, Stillwater likely looks very real. Here is a band looking to discover its place in the crowded world of music and yet suspicious of how their life onstage will somehow affect their lives off it. In response, the band unwittingly solicits the help of William — the young, starstruck rock journalist — who might just illustrate them in the pages of Rolling Stone not as who they are but as they would like to see themselves.

It’s a tightrope of a magic act, and the audience is along for the cross-country ride in order to determine how the final versus-chorus-verse nature of the film will conclude. Just like Stillwater — who at some level must understand that the end of the road is always near — the characters in Crowe’s film should discover how to be content in living in the now.

For those who have never performed a drum solo in a garage band or put a paint brush to paper or tap danced in a studio hall or recited a soliloquoy before a hushed audience or sat down to a typewriter to ponder the nature of film …

… There is an art to living in the now, even if it means being almost famous, being almost cool.

The motion picture, then, is both a love letter to rock & roll and a diary entry of a person finding himself in a world for which he wasn’t designed.

(Are any of us immediately designed for the world in which we live? The answer is no.)

Hoffman’s Lester Bangs distills the movie’s entire experience when he professes to William that a wall exists between the so-called rock star & the so-called rock journalist, between the so-called golden gods & the so-called poets that write of them:

“The only true currency in this bankrupt world,” Bangs tells William in a late-night telephone confessional, “is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool.”

That’s the nature of the story: that we are always in conflict with the world in which we would like to live and the world in which we must, always yearning to be a rock star despite the destination that the tour bus already has in store. That’s what allowed the members of Stillwater to invite William into their fold: because William viewed Stillwater from the perspective of a fan. William saw Stillwater as they hoped they would be seen.

“Maybe we don’t always see ourselves as we are,” Russell mumbles in the last moments before Rolling Stone magazine publishes a cover story that the band Stillwater is not as invulnerable as its band members would imagine.

That would certainly make for a great story, great enough even for the big screen.

And – rest assured – the soundtrack would be incendiary.

* * * *

Almost Famous is streaming on Pluto TV.

W I N T E R

T H R I L L E R

* * * *

25th Hour

d. Spike Lee | dp. Rodrigo Prieto | s. David Benioff | 2002 | R | 135 minutes

* * * *

The violent sounds of a dog being beaten make for the disarming introduction of Spike Lee’s 2002 film 25th Hour, a motion picture that says as much about its criminal protagonist Montgomery Brogan (Ed Norton) as it says about the United States of America.

And that’s complicated.

The impressions are both visceral and pathetic, the kind inspiring the viewer to fight back or show its belly. And there’s no better sonic preamble to prepare the audience for a film that tells a story of crime, judgment, reckoning, and hope.

I stumbled upon this motion picture for two reasons. The first was Spike Lee himself. At that time, his 1992 film Malcolm X was one of the best stories of humanity that I’d ever seen; his 2000 film Bamboozled was both sobering and infuriating — Lee would mix the methods with 25th Hour. The second draw was the poster: an image of Ed Norton leading a dog by a leash. The poster’s tagline asks, “Can you change your whole life in one day?” But when I rolled the DVD case over in my hand, I discovered little more than what the poster insinuated but that the film was the first major motion picture filmed at Ground Zero in NYC.

I stepped onto that hallowed ground with the benefit of time & reflection. Perhaps that was the same time & reflection of which other viewers didn’t have the privilege. I get it. Many people survived the events of 9/11 and were asked to watch the first major motion picture shot in the shadow of the World Trade Center. But I hadn’t survived 9/11, like them. I was altogether untouched by the events of September 11th – I had no skin in the game.

But between that day of infamy and the evening that I would sift through the debris of Spike Lee’s divisive film, I’d gained some insight of that day through reading my history books. And that insight has problematically informed my viewing of 25th Hour ever since.

Adapted from David Benioff’s novel of the same name, Lee’s film tells the story of Monty Brogan in the last hours of his free life, a Brooklyn drug dealer who has been pinched and now has less than a day to say goodbye to his family & friends before submitting himself to a seven-year prison sentence. Meeting, then, from dusk to dawn with his lover (Rosario Dawson), his father (Brian Cox), his two best friends (Philip Seymour Hoffman & Barry Pepper), and some of his nefarious business associates, Monty contends with the crimes that he has committed and the judgement that has been bestowed upon him.

Published in 2000, Benioff’s novel obviously has nothing to do with the film’s 9/11 backdrop. That written, Benioff adapted his novel to reflect the NYC of post-9/11 America, the result is compelling, to write the least.

More than any other film showcased here, 25th Hour lends itself to the most interpretative analysis, and those readings demonstrate how complicated the motion picture may be. As complicated as Monty Brogan as the movie’s protagonist himself.

Brogan — an upstart high school basketball player, smaller than all of his teammates and smaller than his opponents — had a lot to prove as a competitor in the world of amateur basketball, even in the world. “Look at what a little punk I was,” Monty tells a high school associate as he stands before a black & white photograph in the lobby of the school, of his teammates & him. The team — youthful, in its prime, ready to take on the world — towers over young Monty.

Way back then, asserting his place in the world, Monty possessed no shortage of potential in besting anyone who got in his way. And for a while, it likely worked. But — unfortunately — Monty pursued an easier path, neither climbing the ranks in a basketball career nor attending college, going into business, doing anything. He chose a more criminal path, paved with money and strong-arming and ignoring forever the path of which he could have followed.

Some would say, just like America.

So Monty – due to his past transgressions – somehow deserves the fate that awaits him: the charges, the trial, the verdict, the sentence. As Monty prepares for a years-long stay in prison, he confesses that he must go there beaten & bruised, ugly, only so that he can survive the years to come. In order to survive the sentence that he has earned, he must be beaten. He must be broken. Only in such a state will he be able to build himself back up, and the scene in which he asks his best friends to abuse him is an emotionally hard watch.

And what’s fantastic about 25th Hour is that as much as it reads like the end for Monty Brogan, this narrative is one of new beginnings, just like the motion picture that begins with the harrowing beating of a dog, an animal that neither Monty nor his criminal colleague can readily identify. Kostya (Tony Siragusa) identifies the mongrel as a pit bull – but Monty isn’t so sure. “I don’t know what he is,” he tells Kostya, saying that the dog clearly lost someone some money to wind up in the pulpy mess of his current state. This outmatched animal, fighting for its life, is otherwise unidentifiable as any single class of dog. All the audience knows of this flea-bitten animal is that it’s on its last legs, growling to establish its right to live.

Just like America.

So Monty entertains the idea of rescuing the dog, of nursing it back to health. “They’ve left him out here to suffer and die,” Monty admits, in the shadows of the WTC attacks, adding, when the mutt barks at him aggressively, “he’s got a lot of life left in him.”

Just like America.

And despite Kostya’s protests that they leave the dog to die, Monty has faith that this thing won’t go toes up tonight. “He’s not ready to go yet,” Monty says, as the two stand over the bloodied dog that will be named Doyle. “He wants to live,” adding that the dog’s beating may be good for him in the long run.

Just like America.

Called simply the United States of America, once upon a time, its name resonates differently today, much like Doyle the Dog earned his name because — according to Kostya — Doyle’s Law tells us that anything that can go wrong, will … even if it’s really called Murphy’s Law. And whatever bad that can happen, will — no matter what you call it.

Monty Brogan. New York City. The World Trade Center attack. Doyle the Dog. Frank Slaugherty (Pepper), an unrefined Wall Street trader with his eye on wealth. Jacob Elinsky (Hoffman), an introverted high school teacher with a diminishing view of his life’s work. Even James Brogan (Brian Cox), a NYC faithful who holds fast to the days of the past without recognizing that his world has irrevocably changed due to his own behavior. In their way, each is a proxy for America, a life story centuries in the making.

“This life came so close to never happening,” Monty’s father intones as his son’s fate is ambiguously concluded in the final minutes of the motion picture. As it turns out, it is a life that needed to — and did — happen.

Perhaps Monty will redeem himself one day — seven years later — having emerged from the prison cell that is, in part, of his own design.

And perhaps emerging from that prison — the day after the worst of it: his conviction, his sentencing, his imprisonment, or 9/11 itself — is how one changes their entire life in a single day.

Again: it’s complicated.

Just like America.

* * * *

25th Hour is available to rent on a number of streaming platforms.

Chris Kaine is the most amateur film essayist whom you may ever imagine. He earnestly contends that he was named after the actor Chris Sarandon, because he was either conceived while his parents watched Fright Night (1985) in his paternal grandparents’ basement, or because of their love for The Princess Bride (1987), which stars a character by the name of “Humperdink,” which is pretty funny, if you think about it.

Leave a comment