This month, the Pickwick looks back on films from the year 2005, movies for which the Pickwick remains thankful.

I came into the world of comic books at an early age, and my introduction to that world came from two very different road maps, and they came from my single mother and my uncle.

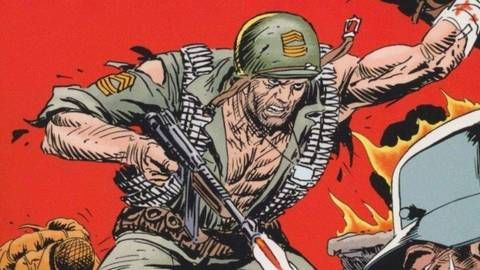

I imagine that most comic book readers’ journeys began out of spandex and mutants, not from shadows and moodiness. For her part, Mom was a fan of the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, heroes who intrinsically came together to defeat evil. She loved Captain America, though she always encouraged me to explore Sgt. Rock.

“[Captain America & Sgt. Rock are] very different heroes,” Mom once said. “But sometimes, a different kind of hero is what we need.”

Mom came from a family of men who had proudly served their country in various ways in the name of democracy, and she never said more than that on the Star-Spangled Avenger or the Howling Commando.

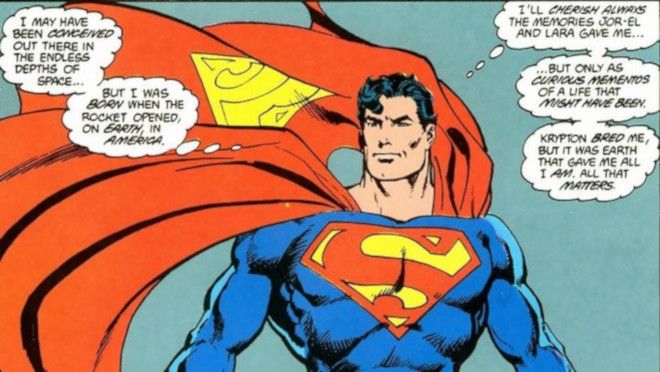

On the other hand, she also never tired of reminding me that Superman’s outfit was composed of at least two colors of the American flag, that the Man of Steel himself was a better embodiment of America than any other comic book character.

“That alien boy is America,” my mother would say of Superman — more to herself than anyone else in the room — sometimes, as we watched Christopher Reeve prove on the small screen that a man could fly.

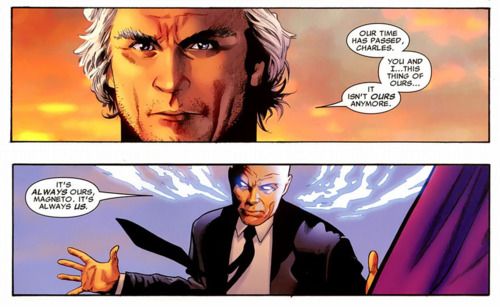

My uncle, meanwhile, was attracted to different heroes and adventures, resisting the bright colors of the best heroes humanity could offer. He appreciated the shadows of the comic book city streets: the moral questionability of Batman and the duality of good & evil that lurked within Bruce Banner & the incredible Hulk. But no other comic book team fascinated my uncle more than the Uncanny X-Men. And I came to love them too. Their exploits disguised their cultural inspirations: the Civil Rights philosophies of Dr. Martin Luther King & Malcolm X, and it was that grounded humanity that drew me to them.

That’s what ultimately demanded me to relate to the X-Men. They were different from the rest of humanity, and yet they protected the rest of humanity.

“They’re weirdos,” my uncle once intoned, “and the world needs its weirdos.”

Maybe that’s why I decided that I was okay, being one.

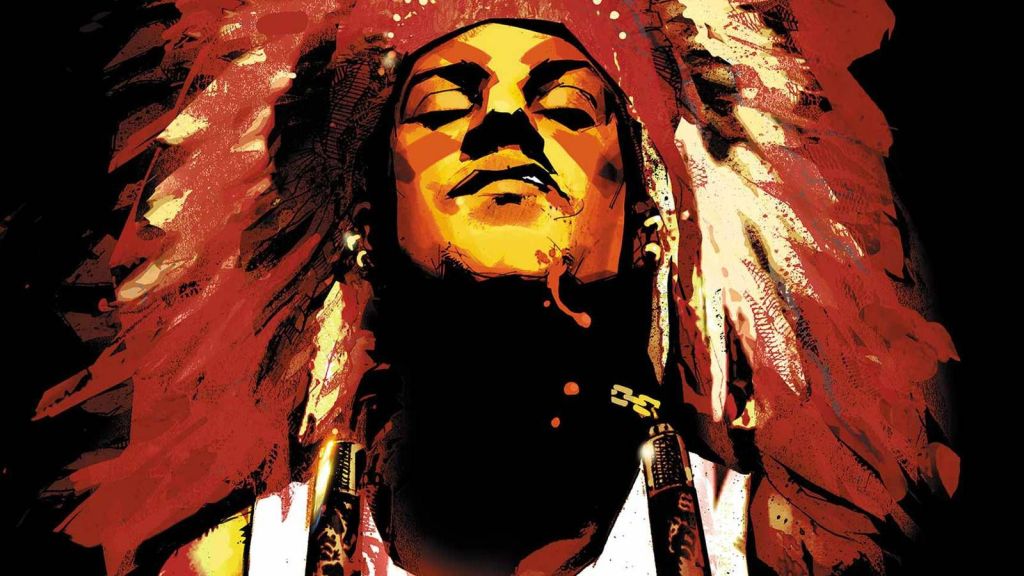

So, while I lamented the fact that I would never be the most traditional hero to be an Avenger at the dinner table, I had a home with misfits like the X-Men. Over time, at all times, I gravitated to stories that illustrated ambiguity similarly, discovering comic books that my mother & uncle seem to have missed: Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles (1994); Marvel Comics’ The Sentry (2000); Mike Kunkel’s Herobear and the Kid (2001), and Vertigo Comics’ Scalped (2007), among others.

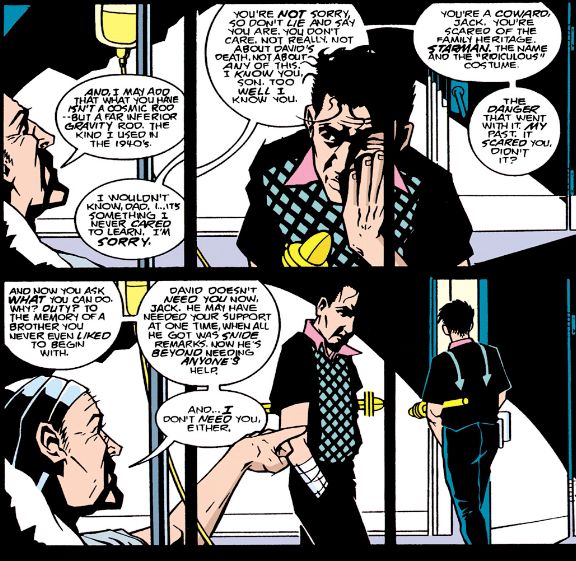

These were stories that were somehow antithetical to the weekday afternoon adventures that superhero comics offered at that time. They pushed the envelope beyond what Batman meant to Nightwing, what Hal Jordan meant to Guy Gardner, what Ted Knight Starman meant to Jack Knight Starman.

Meanwhile, I was introduced to other books & characters by my uncle. I tried reading two issues of DC Vertigo’s Sandman, but I felt like I’d wandered into the fourth act of a Shakespearean tragedy, couldn’t suss out what was going on, and — frankly — didn’t have the patience to stick around.

And that was that.

But my uncle also let me read a single issue (at first) of the DC Comics series Hellblazer.

#27.

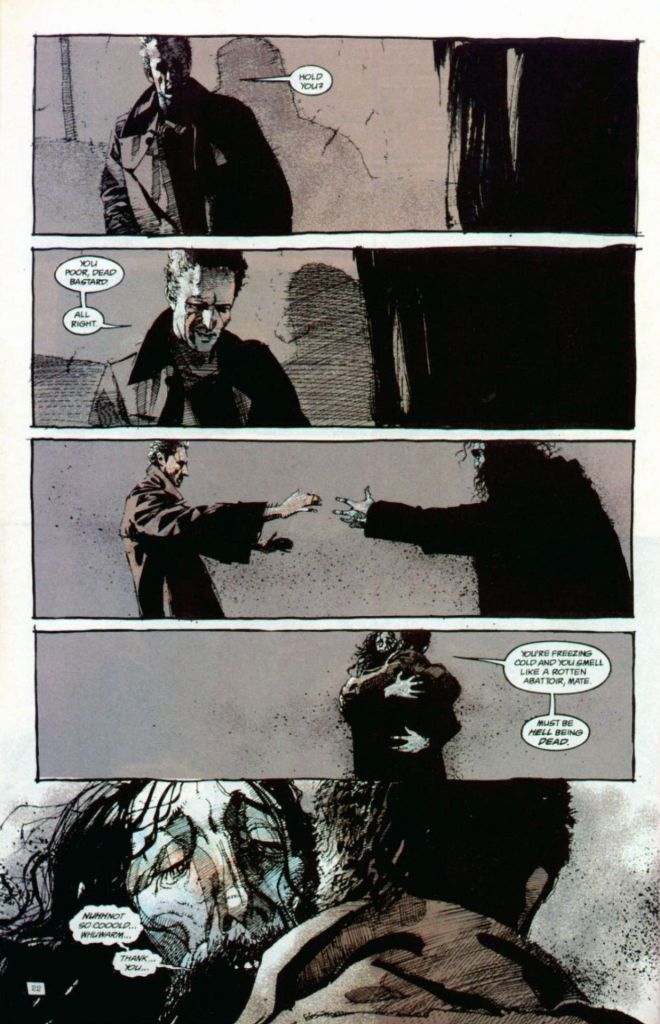

In a single-issue story that has no consequence on the series’ mythology, the anti-hero mage John Constantine deals with his own existential dilemmas as he comes across what appears to be a dead, homeless man wandering the streets of London.

It was written by Neil Gaiman – the same writer who had written the indecipherable saga in Sandman – but my uncle assured me that I didn’t need to know anything about John Constantine in order to be haunted by the story.

So, I read it.

And it haunted me.

And I loved Dave McKean’s moody artwork, having seen it before in my uncle’s hardcover copy of Batman: Arkham Asylum. But more than that, Hellblazer #27 tapped into a sense of loss that I’d never read in the pages of a comic book. Not in the pages of Captain America. Not in the pages of Detective Comics. Here was a hero — for the lack of any other word — who perhaps wanted to do the right thing by the world but felt exiled to a reality in which he never really could. He wasn’t possessed with the inherent good of Superman. He wasn’t possessed with the unfaltering patriotism of Captain America.

But he was possessed by something, and I found that captivating.

I read every issue of Hellblazer after that – from the first issue onward – around Halloween of 2004. And Hellblazer hit at just the right moment for me. I was moved by Constantine’s stay at Ravenscar. I marveled at his ability to trick Hell into giving him a new lease on life. I watched as his friends perished when the First of the Fallen ultimately cornered him. More often than not, Constantine walked between the raindrops, and that’s what I loved about him, because — in his world — it was always raining.

But sometimes, the rain broke through and touched him, and I loved him even more when it did.

My reading, then, seemed perfectly timed to coincide with the release of the Warner Brothers picture in February of 2005, simply entitled Constantine. The film stars Keanu Reeves as Constantine, the seemingly aloof & apparently apathetic mage star of Hellblazer. I wasn’t immediately sold on the casting. Constantine doesn’t surf like Reeves did in Point Break (1991). Constantine isn’t a slacker time traveler with his best friend in tow (1989).

It didn’t help that when I pored through my uncle’s back issues of Hellblazer, the Constantine on the page looked nothing like the Constantine on the big screen. John Constantine was British, blonde, dressed in a beige trench coat, and possessed with a surly misdemeanor. But on the motion picture screen, Constantine was American, raven-haired, dressed in a black trench coat, and in no small measure imbued with a surly misdemeanor.

I guess one out of four isn’t bad, if you’re a fan of the Hellblazer comic book.

The widescreen adaptation follows the street level adventures of L.A. demonologist John Constantine, possessed with a need to rid the living world of Underworld cretins and possessed with the knowledge that he — as an attempted suicide — is doomed to burn in Hell when he inevitably dies.

Constantine lives on borrowed time — due in no small part to his lung cancer, provoked by years of smoking — but when a case involving a dead mental patient and her twin sister detective who believes her sister’s death is suspicious, Constantine could potentially save a young woman’s soul from damnation or save his own soul from eternal torment.

The film flirts with some of the ideas laid out in Garth Ennis & Steve Dillon’s Hellblazer “Dangerous Habits” storyline, but the widescreen adaptation introduced some additional spirits into the cinematic cocktail. And what I loved about the comic book series was precisely what I loved about the movie: I saw my hero in a movie that saw him make a sacrifice like my uncle saw the X-Men make a sacrifice in 2000 and like my mom saw Captain America make a sacrifice in 2011. With Constantine, it occurred to me that people who would later become addicted to superhero movies in the 2010’s could see a different kind of hero in 2005, fighting evil in a dramatically different way, with a character that I’d been with since page one, so to speak.

Only Harry Potter and hobbit fans know elation like this.

But in 2005, I wasn’t privy to the Internet hate that Constantine would confront as well. Many faithful devotees of the comic book were outraged by the surface-level detours that the film took, and while I appreciated both the printed source material and the cinematic adaptation on the screen, I wouldn’t articulate it at 14. For the Hellblazer purists, perhaps Constantine wouldn’t slay demons as it promised. But for those who haven’t read a single page of Hellblazer, Constantine is quite entertaining.

You can separate the two Constantine works of art — the long-running monthly comic book series & the 2005 film — as long as you don’t chain yourself to one or the other.

Dogmatically — even blindly — sticking to one’s faith is one of the many conflicts that Constantine’s comic books & cinematic adaptations have explored.

But most importantly, when I saw Constantine come to life — however he looked, however he sounded — I felt a little gratified that Hollywood had decided to take a chance on something that seemed loved by me alone, like my favorite rock album, like my favorite short story. What was once meant only for me was now available to the world. And while the film deviates in some ways from the written & illustrated page, my response to any big screen adaptation and its deviation from the source material is this: If you want the comic book story of John Constsntine alone — go read Hellblazer. Those stories still exist. I think there’s some grace in allowing IP to transform over time.

A remake, a reboot, an adaptation that takes the character in a new direction — none of these erase what made Hellblazer still as rewarding to me as when I first read it.

Today, I cherish reading those Hellblazer comic books. And I would still read my Superman stories and my Fantastic Four stories and my X-Men stories – but I would save stories like Hellblazer for late at night, just past midnight on a Saturday night, when the wind was inviting the tree branches to scratch against my window pane in the hopes that I would let that dark nature in.

And – today – I love the bravery of the film Constantine, steering just left enough of the comic book series to still be … right.

Disowning either of these works of art – in my opinion – would simply make me a wanker.

And that would be a cold day in Hell.

***

Leave a comment